A month or so ago one of our readers commented on the need for more information on atrial fibrillation, and, since I’m always happy to comply with requests to blather on about anything in this blog, I’ll gladly accommodate.

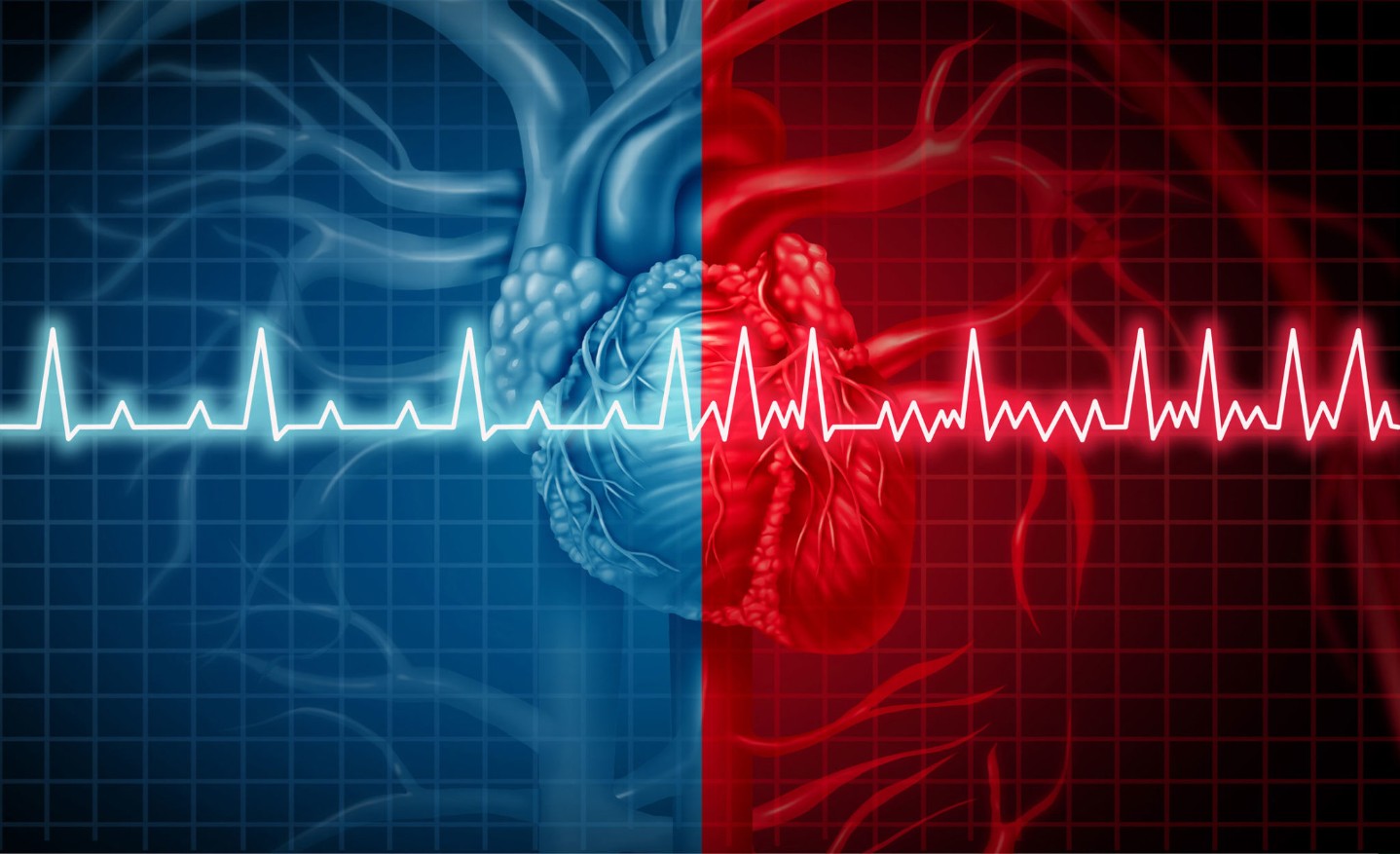

To understand atrial fibrillation (AF) you must first understand how normal electric activity in the heart works. Once every second an area of cells known as the sinus node produces a spontaneous electrical impulse—a minute shock—that spreads throughout the muscle of the top chambers of the heart (the right and left atria). The atria are responsible for pushing blood down into the ventricles, the muscular bottom chambers of the heart that pump blood out to the body and the lungs. The electrical stimulus first causes contraction of the atria and then a split second later (one-fifth of a second to be more precise) makes its way down into the ventricles to cause contraction there. The result is that the atria contract first followed by the ventricles. Lub-dub.

Let me use an example to better illustrate the electrical rhythm of a heart beat. Think of a big band orchestra (a la Tommy Dorsey or Count Basie) with a conductor leading the music, the musicians playing the music, and a room full of dancers. Think of the sinus node as the conductor—constantly tapping out a rhythm, telling the heart to go slower or faster as needed. The musicians represent the atrial muscle and follow the conductor impeccably. Now pretend that the dancers, who in this scenario represent the ventricular muscle, move with the beat of the music. Under normal circumstances the three parts—conductor, musicians, dancers—perform in perfect synchrony.

Now let’s pretend that a clarinetist decides to spin off into an allegretto while the rest of the orchestra is in the middle of an andante. He plays fast and furious, and so loud that the neighboring instruments get confused and start their own solos. This behavior makes its way through the orchestra until all musicians are playing their own tunes, to their own beat. Nothing that the conductor can do will matter since he has lost control of the musicians. The dancers, in turn, hear the cacophony and dance faster and faster, trying their best to keep up with the flood of rhythms they perceive.

This is what happens with AF. The top atrial chambers descend into a chaotic dervish and the ventricles do their best to follow, but tend to beat so fast and irregularly that the person starts to have symptoms of palpitations, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness.

To add to this, since the atria are no longer contracting in a coordinated fashion, the blood that normally courses smoothly through the atria with each squeeze begins to coagulate along the corrugated walls of the chambers. In the left atrium this represents a particular problem since any clot that forms there and breaks free will migrate through the left ventricle and out the heart, coming to rest only when it lodges in a small artery in the brain (causing a stroke) or elsewhere in the body.

Therapy for AF really needs to focus on two areas:

- Decreasing risk of stroke

- Slowing the heart rate

To decrease the risk of clot to the brain we generally employ the age-old drugs warfarin and aspirin.

Slowing the heart rate is a little more complicated. We generally adopt one of two strategies:

-

- Promote normal rhythm. The most common way to do this is to add a medication that pushes the heart toward normal rhythm and decreases the likelihood of AF. For this we frequently use propafenone (Rythmol), amiodarone (Pacerone), sotalol (Betapace), flecainide (Tambocor), and a few others. Adding one of these drugs is like hiring the club’s bouncer to stand over the shoulder of the wayward clarinetist and whack him every time he falls out of tempo.

A second way to keep the patient out of atrial fibrillation is to do an invasive procedure called pulmonary vein isolation (also referred to as AF ablation). In many patients we know where the AF starts (at the inlet of the 4 pulmonary veins) before it expands to involve the whole upper half of the heart. If we encircle the pulmonary veins with a scar line we can insulate the rest of the heart from the abnormal electrical activity of this small area. It’s like taking the troublesome clarinet player and moving him to another room where he can’t bother anyone.

This procedure is done either through the veins (by an electrophysiologist) or through a small hole in the chest wall (by a heart surgeon). Our group offers both approaches.

2. Allow AF to continue but control heart rate. We do this mostly with medications like beta-blockers, calcium blockers, and digoxin. This therapy is akin to allowing the band to play as chaotically as they want but limiting how fast the dancers move.

Most older patients and those with valve problems have hearts that are so stubbornly stuck in AF that we can’t get them back into normal rhythm despite our best efforts. Allowing the AF to continue and simply controlling the rate doesn’t seem as glamorous an approach as rhythm control, but in reality patients can live long and healthy lives with ongoing AF as long the ventricular rate is in a comfortable range (heart rate between 50 and 80 at rest and up to 120 or 130 with activity) and the patient is on some type of anti-clotting medication (aspirin or warfarin). A couple of large research studies suggest that this approach may actually be safer in many people.

Atrial fibrillation is a very complicated issue that we often take for granted because we see it so frequently. With the right medications AF should be no more than a nuisance issue for the patients who suffer from it and they should be able to continue with full physical activity—even if that includes dancing and clarinet playing.